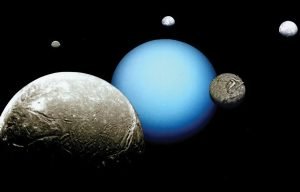

Icy Planet’s Satellites May Be Habitable

Researchers believe that there are oceans of liquid water beneath the surface of some of the moons of Uranus, the seventh planet from the Sun, and that extraterrestrial life forms may exist in them.

Researchers believe that there are oceans of liquid water beneath the surface of some of the moons of Uranus, the seventh planet from the Sun, and that extraterrestrial life forms may exist in them.

For the past two years, scientists have been urging NASA and other space agencies to send a research mission to the moons of Uranus. It is already known that some moons of Jupiter and Saturn contain oceans of liquid water where extraterrestrial life could exist.

The authors of a new article published in the journal Astrobiology argue that some of Uranus’s moons may also harbor oceans and could be habitable.

They propose that extraterrestrial life forms could employ chemical metabolic reactions for survival, similar to those used by certain organisms found on the ocean floor of Earth. The authors also call for an urgent spacecraft to be sent to the moons of Uranus to determine their habitability, according to Space.

Scientists have found clear signs of underground oceans of liquid water on some of Uranus’s moons, with a chemical composition that could support the development of life. Sending a spacecraft there could help establish whether these worlds are habitable and reveal the mechanisms underlying their evolution. In particular, it is essential to investigate what processes help maintain heat within Uranus’s moons, which are far from the Sun.

Researchers reanalyzed data collected by the Voyager 2 spacecraft, which flew past Uranus in 1986. At that time, data was gathered on Uranus’s five largest moons: Ariel, Umbriel, Titania, Oberon, and Miranda.

The data was combined with computer simulations that considered the moons’ size and density, suggesting that Ariel, Umbriel, Titania, and Oberon may contain internal oceans of liquid water located between their cores and icy surfaces.

Due to their distance from the Sun, liquid water within the moons cannot remain in that state for long. However, scientists believe that internal heat generated by the decay of radioactive elements, particularly potassium, uranium, and thorium, helps sustain these oceans in liquid form.

Evidence indicates that Miranda and Ariel experienced geological activity between 100 million and 1 billion years ago. This, along with the gravitational influence of Uranus, may have caused the satellites to heat up internally.

Unfortunately, the same level of heating that keeps Jupiter’s and Saturn’s moons warm is not possible for Uranus’s moons, as Uranus exerts a weaker gravitational pull due to its smaller mass. However, scientists believe that sufficient heat exists within the moons, at least from geological activity and radioactive decay.

According to the authors of the article, a future mission to Uranus’s moons could study their internal thermal conditions, which play a crucial role in the potential for life as we know it.

On Earth, single-celled organisms can thrive at temperatures as low as minus 20 degrees Celsius. Below that threshold, the metabolic processes required for life to extract energy from the environment become increasingly complex.

The five major moons of Uranus have temperatures ranging from minus 213 degrees Celsius to minus 193 degrees Celsius, indicating that interior temperatures would need to be significantly higher for these worlds to be habitable.

We also need to determine the salinity of the underground oceans. If they are too salty, extraterrestrial life may not be able to survive.

Since potential life on Uranus’s moons lacks access to solar energy, it would require a constant source of chemical energy. Organisms on the ocean floor of Earth utilize a form of chemosynthesis, where they harness energy from inorganic chemical reactions to produce food. A similar process may be essential for life deep within the moons of Uranus.

Lastly, we must confirm whether the underground oceans contain the building blocks of life, including elements such as carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen, phosphorus, and sulfur.