The Fermi paradox was created by geniuses over lunch

The question is both totally obvious yet technically deep: “Where are all the aliens?” There are hundreds of billions of planets in the Milky Way alone. Surely some of them must be hospitable. And yet, we never see any aliens! When a group of the world’s greatest scientists sat down to lunch, they challenged one another with this paradox.

It would come to be named after Enrico Fermi, who expressed it in a famously pithy form. Fermi led the world in both experimental and theoretical physics, winning the Nobel Prize at age 37 and inventing the first nuclear reactor. His dining interlocutors were Edward Teller, inventor of the thermonuclear bomb and another certifiable genius; Herbert York, Manhattan Project member and first director of Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory; and Emil Konopinski, another Manhattan Project member and notable physicist.

Note: The following account is based on the recollections of the men involved, which were released in a report many years ago. Fermi died before his account could be collected.

It began with UFOs and missing trash cans

Flying saucers were a hot topic at the time, roughly the summer of 1950. Teller recalled that the discussion began when the men agreed that flying saucers were obviously “not real.” Konopinski brought up a cartoon he had seen in The New Yorker, explaining the vexatious disappearance of trash cans in that city. Bug-eyed little men with antennas were descending in a fleet of circular ships and carrying them away. According to Konopinski, Fermi remarked that it was a reasonable theory, because it independently explained the disappearance of the receptacles and the appearance of the saucers. Touché.

Aware of the vastness of the Universe, the party knew that getting to Earth would take a while. This set them to questioning faster-than-light travel. Teller remembers Fermi asking him the probability that something moving faster than light would be seen within ten years. Teller shot back “ten to the minus sixth,” meaning one in a million. Fermi announced that this was much too low, and the real number was about one in ten. What followed was a sparring match as both men criticized and revised their rough estimates of the likelihood of superluminal travel.

Aware of the vastness of the Universe, the party knew that getting to Earth would take a while. This set them to questioning faster-than-light travel. Teller remembers Fermi asking him the probability that something moving faster than light would be seen within ten years. Teller shot back, “Ten to the minus sixth,” meaning one in a million. Fermi announced that this was much too low, and the real number was about one in ten. What followed was a sparring match as both men criticized and revised their rough estimates of the likelihood of superluminal travel.

Mental math

Physicists love playing mental magnitude games such as these, in which the answer to a problem might be 0.007299 or 299,792. The objective is to come up with a quick and dirty model of the problem, but also to make good enough estimates to arrive at an answer that contains the right number of decimal figures.

Fermi — along with Richard Feynman — was held in awe by mere mortals who could accurately approximate mind-blowing figures. Fermi himself was known for estimating the yield of the first atomic test by dropping small pieces of paper into its blast wave and for standing at the controls of the first nuclear reactor and predicting its performance with a slide rule.

After this, the group recalls that the topics of discussion wandered elsewhere. However, Fermi must have been mentally calculating away all the while. Sometime thereafter he blurted out, “Where is everybody?” cracking up the group.

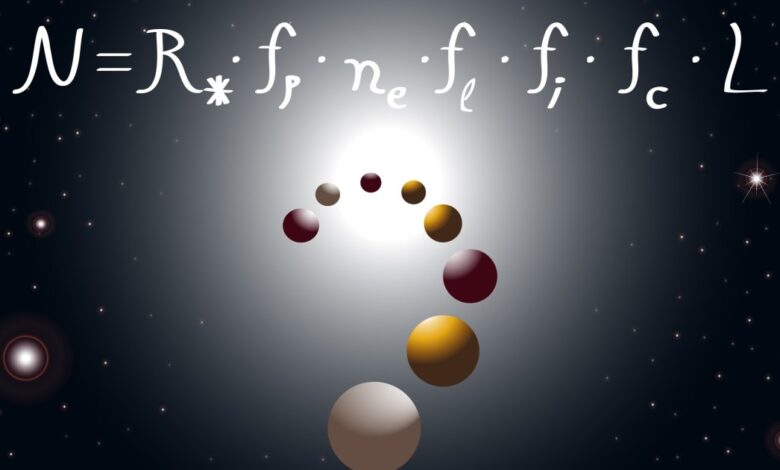

Fermi paradox births the Drake equation

Fermi had just invented and worked through in his head what would later come to be called the Drake equation. The cheeky remark set the men back to speculating about aliens. York recalls that Fermi tossed out the various estimations required to calculate the probability of an alien visit. The group debated the probability of earth-like planets, the duration of technology created by their inhabitants, and similar questions. Fermi calculated that there should be a vast number of technologically sophisticated alien civilizations. Thus, we should be visited frequently.

Given that all present agreed that extraterrestrials were nowhere to be seen, the obvious question was to pinpoint the reason. Teller did not believe in faster-than-light travel. He posited that Earth’s location “in the sticks” explained why no one from the “metropolitan” galactic center made the long flight (thousands of light-years) out to our bumpkin planet. (Would you fly for 10,000 years to see some lower life forms?) York’s memory was fuzzy, but he believed the men settled on the difficulty, futility, or dreariness of long-distance space travel. (Konopinski had no recollection of the follow-on discussion.)

It’s likely that these mental giants reached the same conclusions as most modern thinkers. With so many planets, there should be aliens. Yet, we have absolutely no clue where the aliens are. The problem is so difficult, and so poorly defined, that even brilliant thinkers can make little dent in it.