Scientists think there might be a 2nd type of liquid water

Water is a fascinating substance. It readily manifests on Earth in the three most common states of matter: solid (ice), liquid (water), and gas (water vapor).

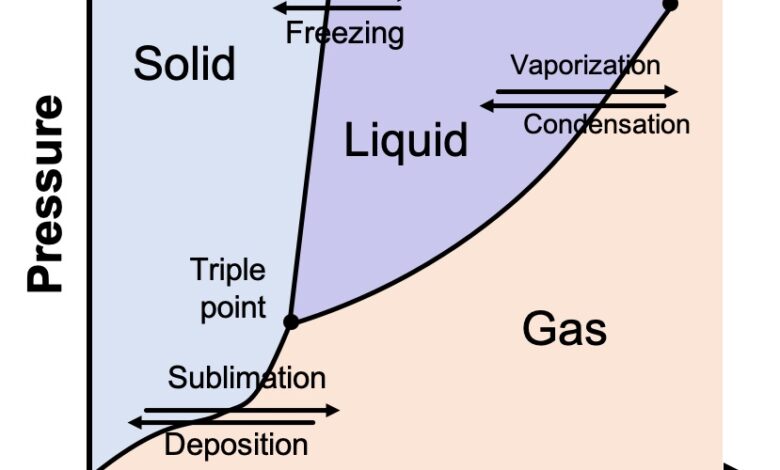

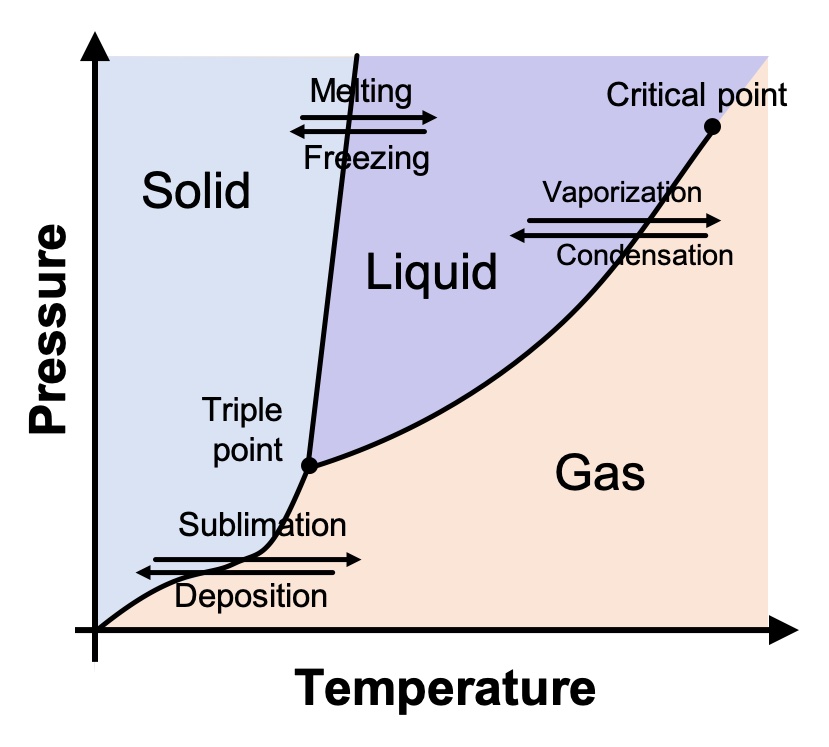

The physicists and chemists who study the various states of matter plot them on a chart known as a phase diagram. A generic one is shown below. On the Y-axis is pressure, and on the X-axis is temperature. The diagram shows what we all know intuitively to be true: As temperatures get colder, things tend to become solid; as the temperature increases, things tend to turn to liquid and eventually gas. This is true not just of water but of every substance.

As we all learned in elementary school, water (at typical atmospheric pressure) above 100° C (212° F) is a gas; between 0° and 100° C (32° and 212° F), it’s a liquid; and below 0° C, it’s solid. But this is only part of the story. Water’s phase diagram is actually much, much more complicated.

Most notably, there are several different kinds of solid forms; that is, water makes many kinds of ice crystals. The ice that we are all familiar with is known as Ih (“one h”), and the water molecules are arranged as a pattern of repeating hexagons. But if we drop the temperature even further, to about -100° C (-148° F), the molecules in the ice crystal re-arrange into a new pattern: a lattice of cubes. This is ice Ic (“one c”). If we keep getting colder, the atoms re-arrange yet again, forming ice XI. This phase has a crystal structure called orthorhombic, a cube stretched so that each side is of a distinct length. If we begin applying pressure, we get yet different types of ice crystals. In all, there are at least 15 forms.

This isn’t unusual. Most chemicals have multiple solid phases. By varying temperature and pressure, atoms and molecules can be coerced into different orientations. Sometimes the properties of one solid phase and another are similar, but at other times they can be very different.

Take tin, for instance. Under atmospheric pressure at room temperature, tin is in the β (beta) solid phase, a shiny metal that is soft but not brittle. But if this β tin is cooled far enough, it will transform into α (alpha) tin, a non-metal so weak that it can fall to pieces under the force of gravity. (See the video.)

Two phases of liquid water

If there are multiple solid states of water, is the same true for the liquid state? Experimentally, it appears that all liquid water is indistinguishable. Every drop behaves the same way at any particular pressure and temperature. Liquid water’s properties do change when pressure and temperature change. For example, liquid water shrinks and becomes densest as it cools to 4° C, but then it expands and becomes lighter as it begins to freeze. But the important thing to note is that all liquid water behaves like this.

Or maybe not. A paper published this month in Nature Physics proposes that there may be a second phase of liquid water. This idea is not original, but the method of mathematically analyzing the water molecules is. The researchers simulate water molecules roiling about in a liquid state. They then increase the pressure in the simulation, forcing the molecules closer together. Within the mass of molecules, they note groups that behave like twisted knots and linked chains.

These shapes can stretch, bend, or move about without breaking their fundamental structure. Two links of a chain remain bound together, regardless of whether the links are moved or if they grow or shrink — unless a ring is torn open. In abstract mathematics jargon, the study of these sorts of shapes and their properties is known as topology.

The possible new phase of liquid water forms when the standard liquid, with molecules generally free to move about, is squeezed into a higher density form in which the molecules are linked together like topological shapes. The researchers show that under certain conditions, liquid water can jump from being described as entangled topological shapes to being described as nearly free from them. This is a phase transition, just like freezing liquid into ice or boiling it into vapor.

But is it real?

Returning from math to reality, this is a testable prediction. If their simulation is accurate, then the density of liquid water should change as they tweak the pressure and temperature — namely, it would get heavier, since the same amount of liquid would fit into a smaller box. But currently, this is just theory. Now, they need to go out and find it.