Dr. Blackburn and the Yellow Fever Plot

In the post 9/11 world, bioterrorism is the stuff of nightmares. During the Cold War arms race, the United States and the Soviet Union developed vast stockpiles of biological and chemical agents.

In the post 9/11 world, bioterrorism is the stuff of nightmares. During the Cold War arms race, the United States and the Soviet Union developed vast stockpiles of biological and chemical agents.

The fear is that terrorists might get a hold of an engineered strain of small pox, anthrax, or the plague and let it loose in a city. Such an outbreak could, at the very least, derail an entire region. At worst, it could end civilization as we know it.

However, this fear is far from a modern preoccupation. Medieval armies would fling plague infected corpses over enemy walls to spread disease, and the scourge of small pox (in some cases intentionally spread) among Native Americans is well documented.

One lesser known incident of bioterrorism occurred during the American Civil War, when a Southern sympathizer attempted to spread Yellow Fever among Northern cities.

Dr. Blackburn: physician… and terrorist?

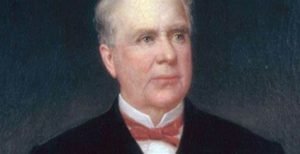

Dr. Luke Blackburn was a Kentuckian, physician, and Southern sympathizer. He was famous for his treatment of yellow fever outbreaks in Louisiana and Mississippi, which made him more than qualified to help when the dread disease broke out in Bermuda.

The year was 1864, and the South was hardpressed in its war against the Union. From the beginning, it lacked the industrial capacity and man power of its northern neighbor, a fact that was taking its toll three years into the conflict.

The Confederacy was desperate for resources, and could ill afford the outbreak in Bermuda, a key partner in its trade network.

So, Dr. Blackburn, eager to help the Southern cause, was duly dispatched to Bermuda, where he offered his services free of charge. Little did his patients know that his expertise was not offered solely out of the goodness of his heart.

Dr. Blackburn gathered their bedding, clothes, vomit crusted rags, and other such disgusting articles. He packed them into trunks, which he put under the care of a co-conspirator named Mr. Swan.

The plan was to ship the trunks first to Halifax, Nova Scotia, and then to New York, Boston, Philadelphia, Norfolk, and Washington where the plague infested articles would be sold to clothing merchants, who would inadvertently spread yellow fever to their customers.

A witness claimed that the good doctor had prepared a valise full of fine shirts for none other than Abraham Lincoln himself.

Since there was no mass outbreak of yellow fever that derailed the entire war effort and handed the South victory, it should be obvious that the whole plot failed.

Witnesses to Dr. Blackburn’s nefarious deeds came forward, and the Union consul in Bermuda got wind of the scheme. The operation was shut down and Dr. Blackburn fled back to Canada.

A futile effort, and its aftermath

When Dr. Blackburn returned to Canada, he was arrested and charged with violating Canada’s Neutrality Act. However, charges were dropped since there wasn’t any hard evidence showing that the plague trunks had ever entered Canada’s border.

In an odd twist, especially in light of today’s attitude toward terrorism and terroristic threats, the US government never followed up on the matter, although newspapers had a field day. While a link to the Confederacy was suspected, any record was destroyed in the wake of the Southern defeat.

As for Dr. Blackburn, he refused to talk about the plot. He continued his work with yellow fever, combating an outbreak in Louisiana in 1878.

He was elected governor of his home state of Kentucky from 1879-1883, where he was held in high regard for his work on prison reform. The only time he spoke on the matter, Blackburn denied all involvement and said that the plot was too ridiculous for a gentleman to be involved with.

It turned out that he was right, in that regard. The yellow fever plot failed from its conception, because yellow fever is can’t spread directly from person to person. Instead, it is spread by mosquitoes. But one shouldn’t be too hard on Dr. Blackburn for that technicality.

First, the germ theory of disease hadn’t be discovered yet. Second, the vector for yellow fever wasn’t discovered until 1911, so there was no way Dr. Blackburn could have known that his little scheme was doomed from the beginning.