Australian Aboriginals Explain the Origin of Desert ‘Fairy Circles’ to Scientists

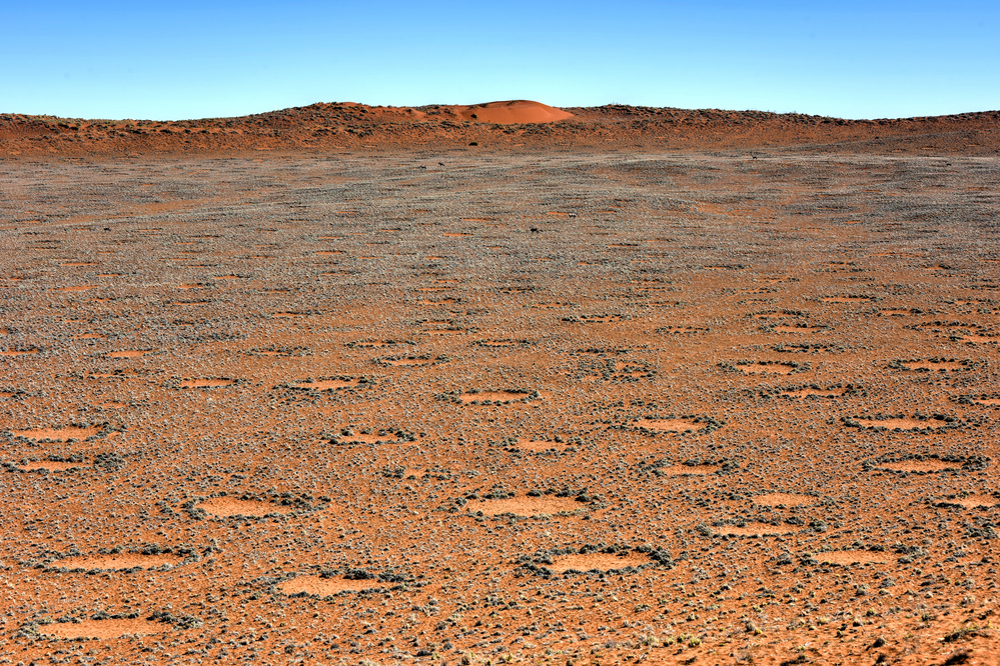

If you moved into a home or apartment and, after settling in, found something strange growing in the backyard, would you ask your neighbors what it might be? Of course you would. For some reason, ecological and environmental scientists in Australia didnt seem to think to ask the local Aboriginals if they knew anything about some strange bare patches appearing in the arid grasslands of the Pilbara region of Western Australia. Some scientists gave these mysterious patches the very non-scientific name “fairy circles” – a name also given to completely different barren circles found only in the arid grasslands of the Namib desert in western parts of Southern Africa.

The native Himba people of northern Namibia called their circles “footprints of the gods” but knew they had real magical powers – they grew grasses in their otherwise barren land and were used for grazing young cattle. The native Australians probably watched as ecologists in 2014 “discovered” the strange circles in their neighborhood and never bothered to get their opinions on what they might be. After coming up with a variety of possible explanations for these “fairy circles,” scientists finally decided to ask the Aboriginals for help. Their answer shocked the scientists. Needless to say, no fairies were involved.

“In the past, when scientists encountered and studied ‘new’ environmental phenomena, they rarely considered the existing knowledge of Aboriginal people. The scientific debate over the regularly spaced bare patches (so-called fairy circles) in arid grasslands of Australian deserts is a case in point. Previous researchers used remote sensing, numerical modelling, aerial images and field observations to propose that fairy circles arise from plant self-organization.”

In a new study published in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution, researchers from The University of Western Australia admitted up front that they and scientists before them should have taken advantage of the thousands of years of knowledge the Aboriginals had of their land. When their scientific predecessors took their first look at these strange circles in the clay in 2014, their inclination was to compare them with the Namibian fairy circles in Africa and look for similarities. While many theories for the Namibian fairy circles have been proposed since they were “discovered” in the 1970s – termites, radioactive soil, plant toxins to name a few – the accepted cause today is that the circles are a consequence of natural competition between grasses for underground nutrients … an explanation that has stood up to the test of time and computer modeling. In 2016, a group of international scientists concluded that the Australian “fairy circles” had a similar cause – they were formed when spinifex plants competed for water and nutrients. The media hailed this theory as a ‘drop the mic’ moment, but no one asked the Aboriginal people of the desert what they thought. Until now.

“These circles, called linyji (Manyjilyjarra language) or mingkirri (Warlpiri language), have been used by Aboriginal people in their food economies and for other domestic and sacred purposes across generations. Knowledge of the linyji has been encoded in demonstration and oral transmission, ritual art and ceremony and other media.”

Led by co-author and ethnoecologist Dr Fiona Walsh, an adjunct at UWA’s School of Engineering, began to suspect that Australia’s clay “fairy circles” were different than Namibia’s sandy ones. Having no other ideas, Walsh and a team of researchers turned to the Aboriginal people of the area around the circles for help. The first thing the native Australians did was get rid of that terrible pseudonym and introduce the scientists to the real name of the circles: linyji (from the Manyjilyjarra language) or mingkirri (from the Warlpiri). Next, they took the scientists on a tour – not of the linyji but of their artworks. (You can see some of them here.) Then, the Aboriginals told the scientists of their native stories about the linyji and what their ancestors taught them to use these circles for. Walsh and her colleagues were shocked … and immediately changed their minds about the former plant theory.

“However, when we worked with Aboriginal people to look at their practices and stories, art and designs, we arrived at a different conclusion. Aboriginal people told us that these regular circular patterns of bare ‘pavements’ are occupied by spinifex termites.”

Perhaps the researchers should have listened to their colleague and co-author Gladys Bidu, who is also a Martu elder. She explained in a university press release that her “old people” told her that the linyji were the homes of the Warturnuma – the big fat flying termites common to the area. While a homeowner might consider termites to be a nuisance at best and a home-destroying wood eater at worst, the Martu had much respect for them.

“We gathered and ate the Warturnuma that flew from linyji. Warturnuma is wama, delicious. Old people also put their seeds on the hard linyji. They hit seed to make damper; our good food.”

According to Walsh, the team followed the instructions of the native Australians and dug 60 trenches 15 cm (6 inches) deep in Nyiyaparli country around the linyji. Despite the ground being rock hard, they found that “100 per cent of them had termite chambers seen horizontally and vertically in the matrix.” Even more surprising (except to the locals), “forty-one per cent of the trenches contained live harvester termites.”

“Termites and termite structures were much more common under the pavements than in the spinifex grasslands next to them which provided alternative scientific evidence to the dominant international theory explaining the ‘fairy circle’ phenomenon in Australia.”

If the native Australians have a word for “Duh!”, they probably used it here. Co-author and termite ecologist, Associate Professor Theo Evans from UWA’s School of Biological Sciences compared harvester termites to krill in the ocean to help illustrate their importance to the desert ecosystems. They are forgotten or ignored (not by the Aboriginals) because they live underground, while the termites that build the huge towering mounds get all of the attention. Unfortunately, they are now a threatened species – Desmond Taylor, a Martu interpreter and study co-author, says his immediate ancestors told him they would find them breeding in the linyji after heavy rains … something he doesn’t see today. Walsh now admits that they never would have found the cause of the “fairy circles” if not for the “clues in the stories of our Aboriginal colleagues and Aboriginal art.” The researchers are committed to not wasting this valuable resource again.

“Aboriginal people refined their encyclopedia and authoritative knowledge when living continuously on this continent for at least 65,000 years and their knowledge is critical to improving ecosystem management and in understanding and caring for Australia’s desert.”

It sounds like linyji are a valuable ecological and historical resource worth saving. A big “thank you” goes to the native Australians for helping these scientists realize it.