First Organism Found That Doesn’t Need Oxygen to Survive

Researchers say this find calls into question everything we know about life on Earth and what it needs.

Researchers say this find calls into question everything we know about life on Earth and what it needs.

The history of the Earth goes back more than 4.5 billion years. Life began to develop the ability to absorb oxygen , that is, to breathe, more than 1.45 billion years ago: a larger archaeon absorbed a smaller bacterium, and somehow this union turned out to be beneficial for both, writes Science Alert.

This symbiotic relationship subsequently led to the two organisms evolving together. Eventually, the bacteria that settled inside became organelles known as mitochondria. In fact, every cell in our body, with the exception of red blood cells, contains a large number of mitochondria, which we need for respiration. It is the mitochondria that break down oxygen to produce the molecule adenosine triphosphate, which multicellular organisms use to power cellular processes.

It is known that some organisms have evolved to adapt to living in conditions of low oxygen or hypoxia. Scientists have discovered that some single-celled organisms have evolved organelles associated with mitochondria for anaerobic metabolism; but the possibility of the existence of exclusively anaerobic multicellular organisms has been the subject of some scientific debate.

That was until a team led by Dayana Yahalomi of Tel Aviv University took a look at a common salmon parasite, Henneguya salminicola. It is known to belong to the same phylum as corals, jellyfish and anemones. The cysts that the parasite forms in fish meat are unsightly, but throughout their life cycle these parasites pose no threat.

The results show that by hiding inside its host, the tiny cnidarian can survive hypoxic conditions. But until this moment, scientists did not understand how he succeeded. During the study, the team examined the DNA of the parasite.

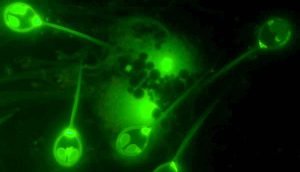

The scientists used sequencing and fluorescence microscopy, which allowed them to closely study the parasite. The team discovered that the cnidarian had actually lost its mitochondrial genome. He also lacked the ability for aerobic respiration and almost all nuclear genes involved in mitochondrial transcription and replication.

Like single-celled organisms, the parasite developed organelles associated with mitochondria, but they were not ordinary ones – their inner membrane has folds that are usually not visible. Note that for comparison, the team used the same sequencing techniques and microscopy in the closely related cnidarian parasite Myxobolusquamalis was used as a control and clearly showed a mitochondrial genome.

Thus, scientists confirmed that there really is an organism on the planet that does not need oxygen at all to survive. Scientists still don’t know exactly how this happened, but they plan to shed light on the mystery of how the parasites managed to move away from their free-living jellyfish ancestors and turn into a much simpler parasite.

It is known that the organism has lost most of the original jellyfish genome, but, oddly enough, has retained a complex structure reminiscent of the stinging cells of a jellyfish. It is known that the parasite uses them not to sting, but to cling to the host.

The authors of the study believe that their results will further allow them to develop strategies that will help protect fish from parasites.