Scientists Discover a New Mysterious Melted Rock Layer Under the Earth’s Crust

The recent powerful earthquakes in Turkey and Syria and the numerous violent volcanic eruptions in recent years make it clear that geologists and seismologists have a long way to go in understanding the causes of these seismic events, how to predict them and perhaps even how to stop them or slow them down to prevent the tragic loss of life and horrific destruction they cause. The recent discovery that the Earth’s iron core has nearly stopped spinning is a good example – scientists disagree on why it spins, why it stopped, when it might start again and what effect this has on the surface of the planet and immediately below it. Another discovery this week may offer more clues. Scientists at the University of Texas at Austin (UTA) have found a new layer under Earth’s crust called “melt” which is comprised of hot molten rocks and may remove some of the mystery behind the movement of tectonic plates.

“The asthenosphere plays a fundamental role in present-day plate tectonics as its low viscosity controls how convection in the mantle below it is expressed at the Earth’s surface above.”

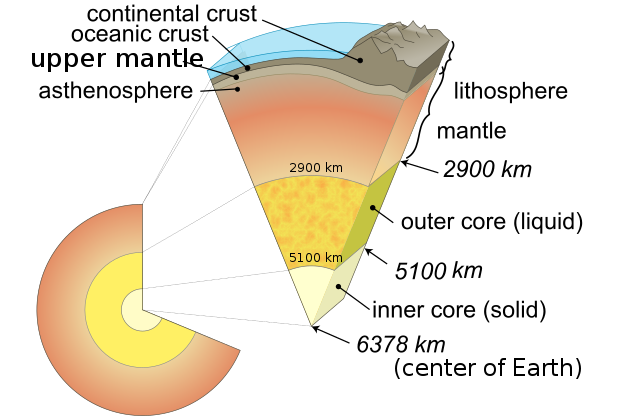

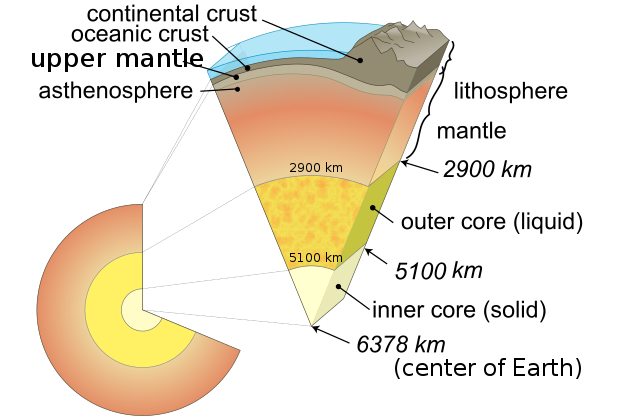

The new study, “Asthenospheric low-velocity zone consistent with globally prevalent partial melting,” published in the journal Nature Geoscience, is written by scientists for scientists, but the press release may help in understanding this important geological discovery. This molten “melt” layer lies about 100 miles below the surface – 95 miles deeper than the world’s deepest well. Seismologists have known of patches of “melt” but the research by the University of Texas at Austin is the first to show it is a layer that completely surrounds the planet. It is referred to as the “asthenosphere” (from the Ancient Greek words for ‘without strength’) because is a soft and shifting layer below the lithosphere, which is the crust and upper mantle of the planet. The asthenosphere is estimated to lie between 50 and 120 miles (80 to 200 km) below the surface and extend as deep as 430 miles (700 km), but this depth is not consistent. While it is referred to as “melt,” the asthenosphere is almost solid with less than 0.1% of it liquid or molten rock, but that is enough to provide the weakness that gives it the name “without strength.” As one might expect, this is the primary source of the magma which oozes or blasts out of volcanoes.

“The origin of the asthenosphere, including the role of partial melting in reducing its viscosity and facilitating deformation, remains unclear.”

While it may sound like scientists understand the “melt,” they admit at the start of the study that they don’t. this is one reason why we have no reliable means for predicting the movement of the tectonic plates directly above the asthenosphere which cause earthquakes and tsunamis and contribute to volcanic activity.

“We were amazed by how well the observation…matches our intuition. I was also a little surprised by how widespread it is.”

Junlin Hua, a postdoctoral fellow in geosciences at the University of Texas, Austin, and lead author of the study, tells Motherboard how he accidentally uncovered new information about the extent, depth and consistency of the “melt” while assembling a global map of the asthenosphere using a database of seismic waves from earthquakes at hundreds of different locations around the planet. As the waves pass through the Earth’s upper layers vertically and horizontally, their interaction with them reveals their materials and properties. Hua’s “Ah-ha!” moment came ironically from data on Turkey.

“I was studying Turkey at that time, and found a seismic signal that marks the lower reach of a seismic low-velocity layer there. People have been talking about the upper boundary of the low-velocity layer a lot, but the lower reach is less mentioned, and I was surprised by that clear lower reach in Turkey.”

Hua noted that seismic waves under Turkey slowed down when they hit what turned out to be a hidden layer of melted rock at a depth of 93 miles (150 km) below the surface. Hua’s team called it the “PVG-150” zone for “positive velocity gradient at 150 kilometers.” As good scientists do, they then looked to see if they obtained similar results in other locations … and found that the PVG-150 zone of partially melted rocks is widespread. If you know anything about oil and viscosity, you know that a thin layer of oil between two surfaces allows them to move without friction. Could the “melt” be the key to the movement of tectonic plates around the world?

“When we think about something melting, we intuitively think that the melt must play a big role in the material’s viscosity. But what we found is that even where the melt fraction is quite high, its effect on mantle flow is very minor.”

So, the researchers admit that they don’t know why the asthenosphere is soft or what causes the “melt,” but they have determined that it plays no part in plate movement. While that may sound like a non-discovery, it allows scientists to eliminate “melt” as a variable on plate tectonics. Then … why is it there and what is it for?

“We can’t rule out that locally melt doesn’t matter. But I think it drives us to see these observations of melt as a marker of what’s going on in the Earth, and not necessarily an active contribution to anything.”

Coauthor Thorsten Becker, who designs geodynamic models of the Earth at the Jackson School’s University of Texas Institute for Geophysics, says we should look at melt as an indicator of activity rather than an initiator of activity. The next place the team wants to study this indicator is at the bottom of the oceans, where the crust measurements are different and seismic waves have different effects. Different instruments will be needed to capture this data.

While this seems like a nothing-burger of a discovery in that it didn’t do anything to help predict the catastrophic earthquake in Turkey and Syria, it actually provides a great deal of knowledge to one particular group of scientists – those building models of what to expect as we search for extraterrestrial life on other planets. In particular, how this melt and the movement of the tectonic plates may have provided the spark of life on Earth.

It’s hard to look at earthquakes and volcanoes as learning experiences, but learn we must if we are to survive on Earth … or find another place to live.